February 27, 2022

This week, we have a guest post from author and early childhood educator, Judith Frizlen. You can visit Judy’s website here!

Young children don’t think their way to learning; they learn by doing. And what they do and how they learn is play. Whatever it takes to learn a skill they need to be able to do what they want to do, they will figure it out. Their interest in the world drives them to explore their capacities and to practice, practice, practice.

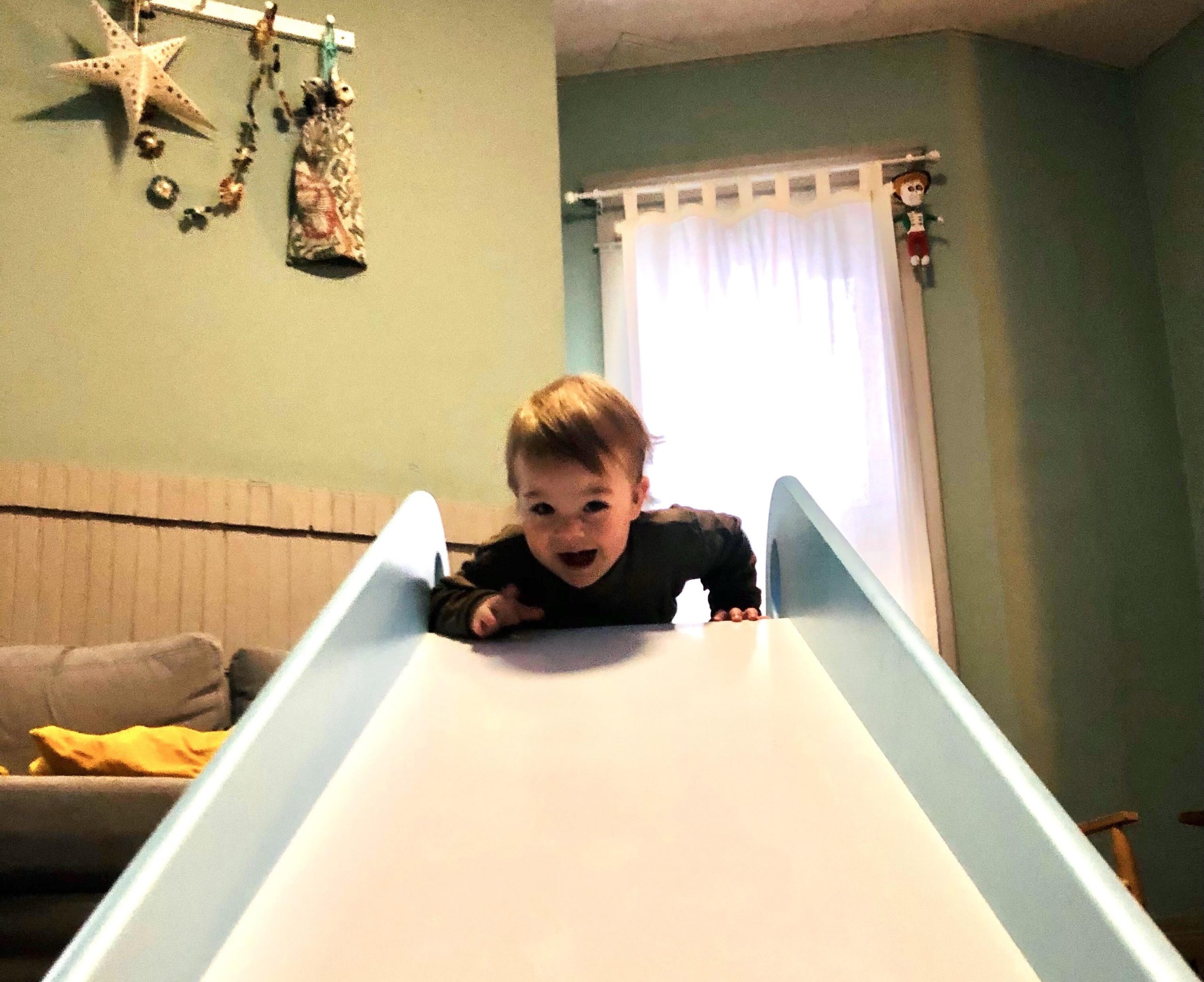

I’ve been watching my grandson learn to master the wooden slide that his parents introduced into their indoor play area. Winter is long in our neck of the woods and gross motor activity is key to the development of the young child.

The grandsons are one and a half and three-years-old. They want and need to move and inhabit their physical bodies. A slide in their home gives them the opportunity to practice gross motor skills, balance, and perseverance.

When the slide first arrived, the three-year-old climbed up and slid down. Yippee! He has the gross motor planning skills necessary to achieve what’s involved in doing that. The one-year-old is engaged in a process of learning how to do just that.

We’ve watched him learn to climb up the stairs while holding the sides and then slide down belly first with his arms out to catch him at the bottom. He has also climbed up the front of the slide skipping the stairs all together, laid belly down and slid feet first to the bottom.

All the while, the adults, who put a cushioned mat around the slide for safety’s sake, observe his process. They watch him experiment and practice what he can do. They trust that one day, he will climb the stairs to the top, swing his legs over one at a time so he is sitting on his bottom and slide down feet first!

Of course, the adults also know they could sit him on top of the slide in the right position to go down feet first.

But what would he learn? He would learn that adults are big and strong and capable. What do we want a child to learn? That he is big and strong and capable, that he can learn incrementally how to master a new skill.

When I founded and ran a LifeWays early childhood center, the play-based curriculum supported children’s physical development. And teachers learned mindfulness – how to be present while the children played. One of our guidelines was not to put children on anything they cannot climb on to themselves.

If they cannot get up there on their own, they are not ready to be there. Although a child may be able to sit and slide down independently, if they cannot climb up and into a sitting position, it is not safe for them – yet.

What is there for the adult to do if we are not “helping” children achieve their goals? We are allowing them to find their way, develop gross motor skills, and a can-do attitude.

We do that by being a calm and confident presence. The children absorb adult attitudes like a sponge absorbs water. A calm and confident presence says to them we know they can do it, with practice, they will get there. We trust their development.

On the other hand, if fear drives us to hover over them, to instruct them in how it’s done or physically manipulate them, they receive another message. That is, you cannot figure this out on your own, you are not safe, you need my help.

Is that the message we want to send? How do we sit on our hands and calm our fears while observing children’s play? I acknowledge, it can be scary sometimes to watch them test out new skills.

I suggest three practices to develop the capacity to be a calm and confident presence:

- Understand the purpose and benefits of play. The more we know its value, the easier it is to support it with confidence.

- Practice belly breathing. Put your hand on your belly and watch it expand when you breathe in and contract when you breathe out. It will calm your fears and keep you centered.

- Use skillful communication to encourage your child. Instead of instructing or praising, use simple expressions like “You did it!” when they accomplish one of their goals. Avoid judgments like “good job” or “well done”; the achievement itself has value without qualifying it and it belongs to the child.

All children have the right to play. They are all capable of learning by doing. A calm and confident presence in the room supports children’s play.

As a matter of fact, the practice of being a calm and confident presence has benefits of its own. Let’s face it, fear is a constant and we might even be afraid of our fear, so learning to acknowledge it and become a calm and confident presence is a valuable life skill.

Try playing with it; you might find that while your calm, confident presence grows, your fears have less power to dominate you. That’s a way of being worth learning and sharing.

Sharing is what we are doing when we are calm and confident in the presence of our children.